Schistosome species, parasite development, and co-infection combinations determine microbiome dynamics in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata

- Dec 15, 2025

- 4 min read

By: Ruben Schols, Cyril Hammoud, Karen Bisschop, Isabel Vanoverberghe, Tine Huyse & Ellen Decaestecker

Why did we do this study?

Schistosomiasis is a snail-borne parasitic disease that affects more than 200 million people worldwide. Despite sustained control efforts and effective diagnostic tools, the disease remains widespread - particularly in tropical and subtropical regions – and is now expanding into Southern Europe. Currently, no effective vaccine exists against schistosomiasis, and control efforts mainly depend on preventive chemotherapy and snail control, highlighting the need for novel and sustainable control measures.

Recent evidence suggests that bacteria may play a key role in shaping host susceptibility and transmission dynamics, as links between microbial communities, disease resistance, and vector competence have been established in other host–parasite systems. To better understand the complex interactions driving snail–schistosome compatibility, microbial communities must be examined across different parasite exposure conditions and developmental stages.

What did we do?

Snail samples (Biomphalaria glabrata) were obtained from exposure experiments involving three schistosome populations (two Schistosoma mansoni and one S. rodhaini). The (co-)infection status of each snail was determined via diagnostic PCRs and metabarcoding. This experimental setup allowed us to explore microbial aspects of the snail-schistosome interaction in unprecedented detail.

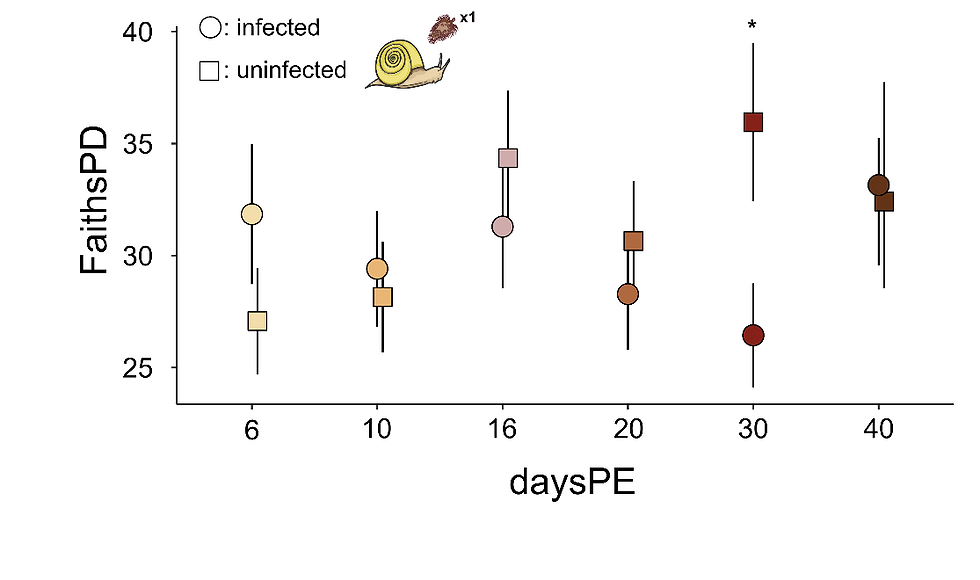

By characterizing the bacterial component of the microbiome based on partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing we discovered that uninfected snails had a significantly higher alpha diversity compared to infected snails but only 30 days after parasite exposure, which coincides with the release of parasites into the environment (i.e., cercarial shedding) (Fig. 1). The drop in diversity could stem from tissue damage and biochemical stress associated with cercarial emergence, from shifts in microbial load relative to increasing parasite DNA, or parasite induced changes necessary for the onset of cercarial shedding. However, no clear signs of dysbiosis were detected at this stage, and bacterial load reductions were not significant. These findings suggest that the microbiome responds subtly but specifically to the transition from parasite maturation to cercarial release, reflecting a complex snail–parasite–microbiome interaction.

We observed dysbiosis in snails infected with S. mansoni but not in those infected by S. rodhaini (Fig. 2). The difference is likely driven by species-specific developmental patterns and adaptations to their natural snail hosts, since S. mansoni naturally infects B. glabrata. Our results suggest that host adaptation determines the extent of microbiome disruption, indicating that disrupting the host microbiome could offer benefits to the parasite.

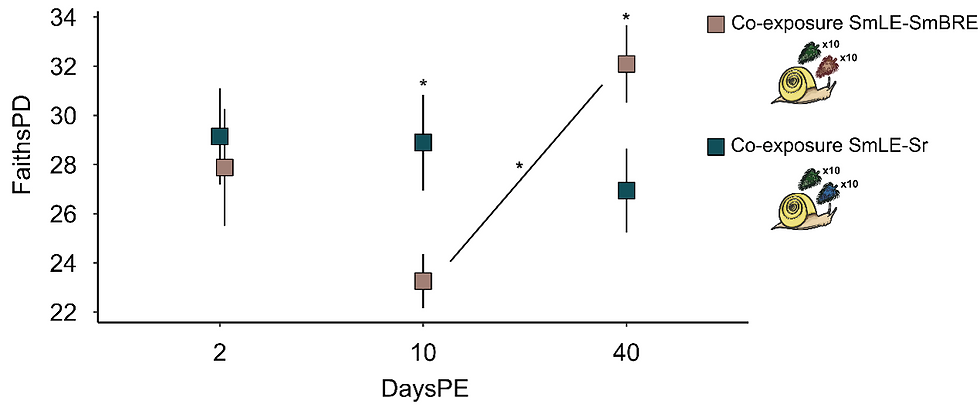

Furthermore, co-infection experiments showed that one of the two S. mansoni populations (LE) generally outcompeted both the other S. mansoni population (BRE) and S. rodhaini. However, its impact on the microbiome varied depending on the co-infecting species (Fig. 3). Specifically, we hypothesize that S. rodhaini may exert a moderating influence on microbiome structure, potentially mitigating the dysbiotic effects of more virulent S. mansoni strains. The findings also suggest that even outcompeted or dormant parasite populations can shape microbiome dynamics through indirect interactions.

The data presented here expand the limited knowledge of the tripartite interaction among snails, parasites, and their microbiomes. They provide a foundation for targeted microbiome manipulation and transplant experiments aimed at resolving causal relationships between microbiome composition and parasite resistance in medically relevant snail hosts. We emphasize that infection status, parasite identity, and prior parasite exposure shape bacterial community structure, underscoring the importance of precise infection diagnostics in future microbiome–parasite studies.

“High-performance computing resources provided by the Flemish Supercomputer Center (VSC) were essential for processing and analyzing these large-scale 16S rRNA gene sequencing datasets. The computational power enabled efficient data cleaning and exportation of files for further analyses in R, while freeing up my personal laptop for other work.”

Read the full publication in Springer Nature here

🔍 Your Research Matters — Let’s Share It!

Have you used VSC’s computing power in your research? Did our infrastructure support your simulations, data analysis, or workflow?

We’d love to hear about it!

Take part in our #ShareYourSuccess campaign and show how VSC helped move your research forward. Whether it’s a publication, a project highlight, or a visual from your work, your story can inspire others.

🖥️ Be featured on our website and social media. Show the impact of your work. Help grow our research community

📬 Submit your story: https://www.vscentrum.be/sys